November is Native American Heritage Month and Florida is rich in indigenous history. With several historic groups of indigenous peoples, Florida’s was – and is today – a land of plentiful resources. When we protect our land and water, we protect our history.

In the Aucilla River area, Suwannee artifacts have been found dating back 15,000 years. Researchers have also found bones of now-extinct prehistoric camelid, bison, and mastodon. In southwest Florida near Tampa, artifacts have been found that date back to 8000 BCE. Archeological sites include settlements by the Tocobaga, Pooy, Uzita, Yagua and Neguarete people, found near Terra Ceia Preserve State Park.

Around 4,000 years ago, Florida began to look like it does today, with sea levels and climate supporting fish, shellfish, and turtles. They developed limited agricultural operations and settlements became more seasonal and were usually located near sources of freshwater. They developed tools and clay-fired pottery for storing, preparing, and serving food. As indigenous groups began to settle and hunt and gather in one specific area, populations grew.

As early as 2,500 years ago, many of Florida’s indigenous groups developed burial mounds. These mounds can still be found across the state today at state parks like Crystal River Archaeological State Park and Letchworth-Love Archaeological Mounds State Park. In southwest Florida, shell middens and mounds were developed from 500 BCE to the late 1400s. Middens are large heaps of clam, oyster, and mussel shells, and other waste such as broken pottery. Middens give researchers a clue into the day to day lives of the people who once lived on Florida’s coasts.

Mound and midden-building tribes included the Calusa, considered to be the first “shell collectors.” The Calusa lived along the inner waterways of Florida’s southwest coast. They used nets and weirs for fishing, collected shellfish, and hunted for animals such as deer. The Calusa discarded their shells or used them for weapons, tools, utensils, jewelry and religious ornaments. In dugout canoes made from cypress logs, they traveled distances as far as Cuba and relied on the Caloosahatchee River, the “River of the Calusa.”

Along Florida’s east coast, the Tequesta also traveled by dugout canoes. The Tequesta lived in present-day Palm Beach, Broward, and Miami-Dade counties, building villages at the mouth of the Miami River and along coastal islands of Biscayne Bay. The Tequesta were hunter-gatherers, relying on fish, shellfish, sharks, and porpoises. They used shark teeth to dig out their large canoes and shells for hammers, fishhooks and other tools. They sometimes traveled great distances to find a delicacy: manatee. The Tequesta also ventured inland where they hunted bear, deer, and wild boar.

In North Florida, the Timucua fished and built seasonal homesteads along Florida’s northeast Atlantic coast. During hot summers, they would fish and collect oysters along the coasts; in winter, they planted crops in inland forests. To manage their maize, beans, squash, melons, and root vegetables, they used slash-and-burn technology to invigorate the soil.

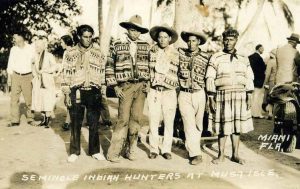

The Seminole Tribe is made up of descendants of many southeastern peoples, including the Maskókî in Alabama. As the United States pushed more and more Native Americans out of their homelands and into Spanish-held Florida, refugees united as yat’siminoli or “free people.” Also among these “free people” were formerly enslaved Africans, who came to be known as Black Seminoles. Many Black Seminoles joined in the Seminole Wars as warriors and translators.

As clashes between the U.S. government and the Seminoles escalated, the two groups engaged in the three Seminole Wars, lasting from 1814 to 1858. A peace treaty was never signed. Through a slow push southward and vast loss of territory, the Seminoles retreated to Lake Okeechobee and the Florida Everglades. The descendants of these indigenous fighters are the members of today’s Seminole Tribe of Florida, the Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida, and the unaffiliated Independent or Traditional Seminoles.

Much of Florida’s indigenous history is still yet to be known. When European explorers arrived in the 1500s, diseases and enslavement stamped out most of Florida’s native populations. Unfortunately, much of what we know about Native Americans is told through European accounts. A goal of preserving the lands they once lived upon is to learn more about Florida’s indigenous history. Many known historic sites have been preserved within state and national parks but remaining sites are under threat of encroaching development and climate change. We must act now to preserve these lands and the history they hold.