Imagine your favorite beach. The crash of waves, the sound of sea oats in the wind, the warm sun on bare skin. In the late 1940s through 1960s, the beach experience was not open for all but was instead limited to only White residents and visitors. Historically, Black Floridians were barred from most beaches, but thanks to civil rights leaders on our Atlantic and Gulf coasts, everyone now has the right to enjoy our priceless natural resources.

While much of the nation’s Civil Rights stories are told from Selma and Montgomery, Alabama, Florida’s beaches saw massive protests for equal access and use of our most precious natural resources. Across the state civil rights activists showed up and spoke up against the discriminatory segregation that kept them from enjoying Florida’s beauty. Beach wade-ins garnered attention for the fight for equal rights and helped open Florida’s 2,000 miles of coastlines to ALL residents and visitors.

Via www.NewtownAlive.org

On the West Coast, communities in Sarasota engaged in a 1950s campaign to desegregate beaches. It started in a community called Newtown. In Jim Crow-era Sarasota, African Americans faced menial jobs, racism, and segregation. Religious services were held in homes initially and then sanctuaries, where Black children were educated and the community empowered. Newtown residents had little access to medical and social services and they depended on each other and benevolent organizations to survive. This nurturing self-preservation shaped this community. And their collective strength made waves.

The residents of Newtown wanted beach access, and in 1951, led by Neil Humphrey Sr., Sarasota’s NAACP president, residents challenged the status quo by driving to the “Whites-Only” Lido Beach, walking the shore, and wading into the water. The 1950s wade ins opened an early front in the fight for equality. After a decade of fighting for access into Lido Beach, and suffering harassment and violence from those who opposed them, their hard work paid off. By 1964, Sarasota County beaches were fully integrated.

Wade-ins were also carried out on the East Coast. In Fort Lauderdale, civil rights activists stormed the beaches near Las Olas Boulevard for six weeks. In 1961, Broward County ended segregation at all its beaches. The former “colored-only” beach is now named in the activists’ honor: Dr. Von D. Mizell-Eula Johnson State Park.

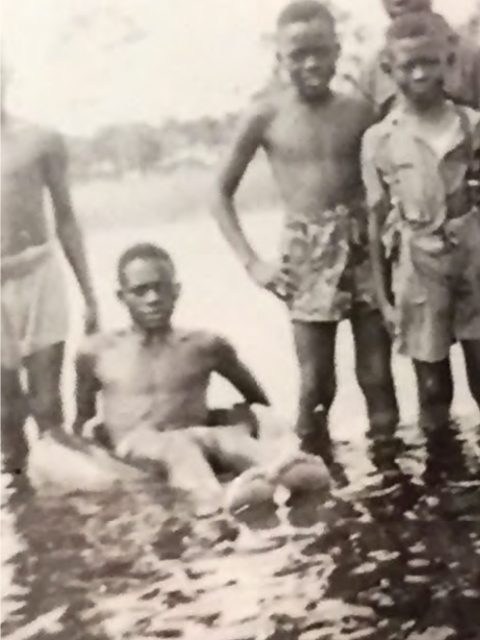

Via Florida State Archives at www.FloridaMemory.com

Before desegregation, Black South Floridians had to drive from Palm Beach and Miami to use Fort Lauderdale’s beaches and by 1946, Broward county acquired a barrier island site, designated it as a “colored-only” beach and promised to make the beach accessible. A road to this new beach was never built and thus Black residents and visitors were still limited from using it. The only way to access the “colored-only” beach was by ferry, captained by Alphonso Giles, the namesake of the park’s boat ramp.

After waiting ten years for the promised road, activists said that enough was enough. Eula Johnson, Dr. Von D Mizell, and others protested at “whites-only” beaches and the City of Fort Lauderdale attempted to get the courts involved in shutting down the wade-ins. The courts entered an order in favor of the activists and launched a larger movement that eventually helped integrate local schools.

Today, this state park near Dania Beach is open for all, providing opportunities to swimming, fishing, boating, hiking, bicycling, and simply connecting with the history and ecosystems that are significant here.

Florida’s beaches are worth fighting for. Thanks to Florida’s civil rights activists, our priceless sandy shores and billowing waves are now accessible to all. The beach not only connects us to the Earth – with its salty, whistling wind and its soaring, crying gulls – but connects us to who we are as Floridians. Everyone deserves open access to our natural resources, and hand in hand environmentalists and civil rights activists are tasked every day to keep them open. Thank you to all who fight for open enjoyment of Florida’s coasts. With all voters and beachgoers in mind, FCV will continue to advocate for access to Florida’s natural resources.

During Black History Month and all year long, learn about the people and places that inspire us today.