It’s no coincidence that communities of color face harsher health burdens due to dirty air and water. From antebellum Reconstruction through the Jim Crow era, housing policy was designed to prevent Black residents from living in predominantly White neighborhoods. Land use decisions about where to locate polluting industries usually placed them in or adjacent to low-income and Black neighborhoods.

Beyond housing policy, banks and other financial institutions engaged in redlining by limiting mortgages to certain customers in certain neighborhoods. A textbook example of institutionalized racism, redlining prevented people of color from buying homes in White neighborhoods, and in fact limited their access to areas with lackluster or failing infrastructure, proximity to dumps and hazardous waste sites, and places with high transportation and manufacturing-related air pollution.

A legacy of Jim Crow-era discrimination, redlining began to divide cities in 1917 after patently exclusionary zoning laws were deemed unconstitutional. Racially restrictive real estate agreements gave power to White communities to limit who was and wasn’t allowed to live in their neighborhoods. By 1947 when these agreements were ruled unconstitutional, the practice was so widespread that it was hard to identify, invalidate, and reverse (if you look closely at the covenants and deed restrictions of your city’s historic neighborhoods, you often can still find them today). The epitome of the institutionalization of the discriminatory practice of redlining came in 1934 when the Federal Housing Administration began using “residential security maps” to make decisions about mortgage refinancing and loan opportunities. These maps clearly demarked wealthy White communities as good investments and communities of color as bad or risky investments. Read more about how maps were color-coded here.

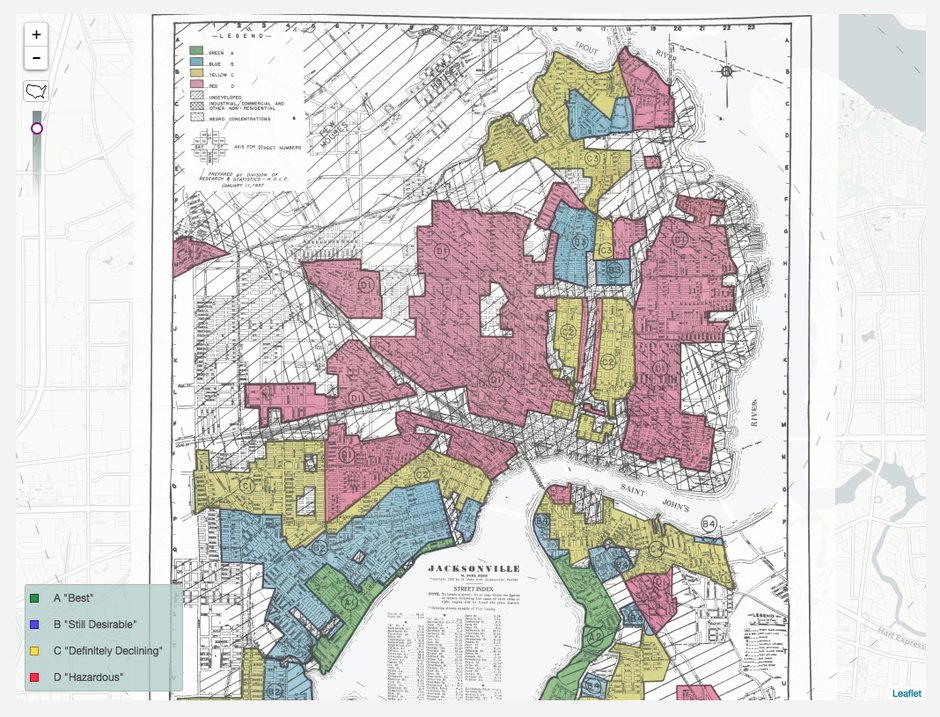

The Fair Housing Act of 1968 prohibited racial discrimination and legally ended redlining, but that doesn’t mean that the legacy of this racist policy isn’t still prevalent today. Looking at maps from Mapping Equality, we can see remnants of redlining still at play today in many Florida communities like Jacksonville, Orlando, and Miami.

In Jacksonville, areas were color-coded as “Best,” “Still Desirable,” “Definitely Declining,” and “Hazardous.” The maps used by banks were drawn with the singular purpose of preventing Black families from moving into White neighborhoods. According to CityLab, Jackonville home mortgages still follow neighborhood lines that banks used 80 years ago. Even though it is illegal to discriminate by race in housing and real estate, continued use of these maps is evidence that racism is so deeply embedded in our institutions and continues to harm people of color today.

Per CityLab: “In the early 20th century, LaVilla and Sugar Hill were upscale black neighborhoods in Jacksonville visited by the likes of Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, and Zora Neale Hurston. The area included a 30-acre park and stately homes for members of Jacksonville’s black professional class. Nevertheless, in the 1930s, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) deemed LaVilla and Sugar Hill—along with other predominantly black neighborhoods—as hazardous or in decline. So-called hazardous areas “embrace[d] principally the Negro areas of the city” including “a community of the best class of Negros,” as HOLC described them at the time.”

You can visit Mapping Equality to see the vestiges of redlining in your community. This interactive site was built by a team of scholars from four universities and looks at 150 cities. Take a close look and see how neighborhoods were ranked as “desireable” or “high restricted” and click to find out why.

Redlining allowed banks to discriminate, on the basis of race, who was allowed to have a mortgage and where. Redlining gave power and legitimacy to wealthy, White bankers, realtors, and appraisers to decide how communities would look and function, all to the detriment of communities of color.

“Black people were viewed as a contagion,” writes Ta-Nehisi Coates in Case for Reparations. “Redlining went beyond FHA-backed loans and spread to the entire mortgage industry, which was already rife with racism, excluding black people from most legitimate means of obtaining a mortgage.”

Institutional racism limited—and still limits—many families’ abilities to build generational wealth. If a family was excluded from homeownership, they may not have been able to maintain long-term leases, invest in businesses by using home equity or send their children to high-quality public schools. With each discriminatory set-back, people of color were excluded from social mobility and the American Dream.

While we celebrate the victories of Black History—the Civil Rights Movement, successful Black-owned businesses, and inspiring and influential Black leaders—we must acknowledge the gravity and legacy of institutional racism that still shapes our state today.

FCV believes that every Florida family deserves clean air and water, access to parks and green spaces, and affordable, clean energy. To achieve environmental justice for all people and the planet, we must address our state’s history of systematic discrimination and dismantle institutions that continue to uphold racism today.